The “Wooden wonder” and forgotten history

The J22 fighter aircraft didn’t make an international breakthrough in the same way as SAAB’s jet aircraft would. It should be pointed out that the international fame enjoyed by the SAAB jet was not normal. Most military aircraft make only a small impression, especially if they are not available for export or tested in battle. But even the Saab 37 Viggen (Thunderbolt) and to some extent the Saab 32 Lansen (Lance) are well known in international aviation circles, despite the fact that they were never exported beyond Sweden’s borders. This, if anything, shows the extreme impact the Swedish aviation industry has had from the 1950s to the present day. For the outsider, it seems as if the Swedish aviation industry almost appeared from nowhere. But its foundation lies under the war years of crisis when the industry had to learn to improvise, utilise what it had in the best possible way and optimise its use of resources and performance while maintaining quality.

But it was not only Sweden that was forced to think creatively in respect of aircraft production. Many other countries, including Germany and Japan, both of whom experienced increasing difficulty in obtaining such important materials as aluminium for their aircraft. In addition, the Japanese were skilled at optimising the performance of their aircraft to get the most possible out of them in respect of speed and manoeuvrability. The Mitsubishi AM6 “Zero”, that for a brief moment was also on the cards for Sweden, is an example of this. The price however was that there was no armour protection for the pilot or for the fuel tanks.

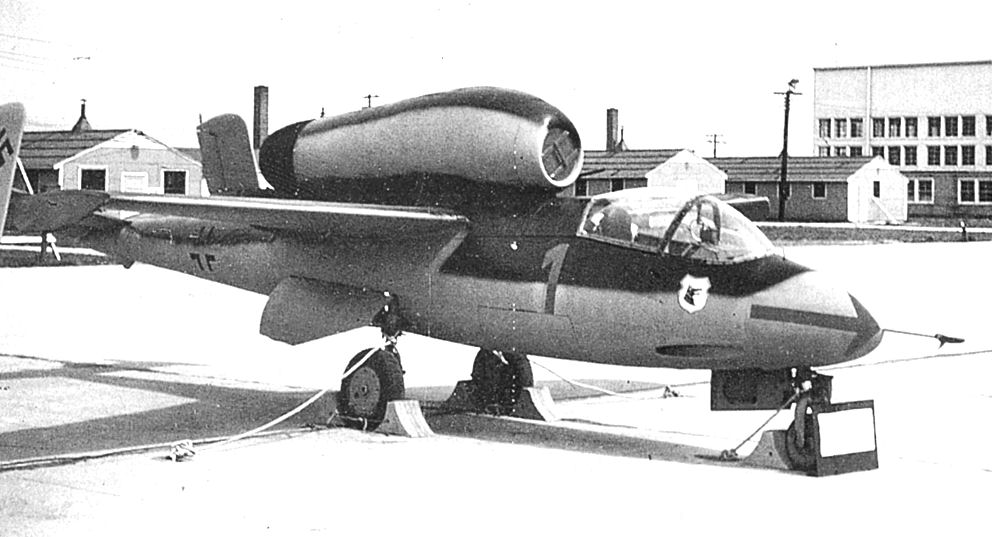

Nazi-Germany was perhaps the one with the most ambitious project when it came to making aircraft in wood. The aircraft in question was the Heinkel He 162, a jet. The ambition was to bring out an aircraft that required the least possible use of strategic materials, was cheap and easy to manufacture, and could be flown by pilots with little experience. Plywood made up most of its construction. It turned out that the aircraft had good performance but required an experienced pilot, which ruled out the idea of using quickly taught youths. Also, the plywood used at the start was of poor quality. However they went into battle at the beginning of 1945 and were appreciated by experienced pilots as a remarkable jet aircraft. Many of the problems which plagued construction were due to haste on the part of both development and production, but the basic design was excellent.

A He 162 that had been captured by American forces in 1945. Photo US Air Force

The “Wooden Wonder”

It may seem to have been a truly desperate measure to use plywood as the principal material for aircraft construction when building a modern jet aircraft in 1940 but the truth is that the J22 was not the only combat aircraft to be built with wood as a major component. In addition it was not that the result was a poor or dangerous aircraft. This was proven by the British manufacturer de Havilland that was struggling with the same problem as Bo Lundberg. De Havilland had as early as 1938 started work on a fast twin-engined bomber. The idea was to mainly use wood, as there would be shortages of steel and aluminium if war broke out. De Havilland was supported by Air Marshal Wilfrid Freeman who also understood that in the event of war strategic materials would be expensive, whereas there was plenty of timber available.

The de Havilland company set to work and brought out a prototype which showed tremendous performance, although many British Air Force staff were sceptical and in 1940 it began to look as if the project, called the DH 98 would be stopped. Lord Beaverbrook, Minister of Aircraft Production called the project “Freeman´s Folly” since Freeman fiercely defended the de Havilland project against several attempts to stop it. A fast bomber was, in 1940, a long way down in the list of priorities, but since de Havilland had also projected a fighter variant they were allowed to continue. 1940 was a dark war year for Great Britain and it was obvious that every fighter aircraft that she could get was needed in the fight against the German Luftwaffe. Despite this, Lord Beaverbrook decided that the project should be cancelled in the summer of 1940.

However de Havilland’s General Manager, L.C.L. Murray, promised Beaverbrook that there would be 50 fighter versions of the DH 98 Mosquito ready by December 1941 at the latest, thereby managing to persuade Lord Beaverbrook to permit continued development. The aircraft was large enough to carry airborne radar, which meant that it could become a valuable night fighter. The armament would be four 20 mm cannons and four 0.303 inch machine guns.

It turned out that the prototypes were very agile and also fast. In fact the Mosquito was faster than Britain’s best fighter, the Spitfire, and also faster than anything the Germans had. The unarmed bomber version had a top speed of 624 km/h (388 mph) while a Spitfire Mark II could reach 590 km/h (367 mph) in 1940-41.

The first Mosquito aircraft entered service on November 15th, 1941 so Murray’s promise to Beaverbrook was not kept. The aircraft was a success among its aircrews and showed itself to be a really efficient machine in everything it did. Night fighting, ground and shipping attack, hit and run bombing raids, bomber pathfinding and fast reconnaissance. It received the nicknames “Mossie” and “The Wooden wonder”, and became one of the most important combat aircraft in the Royal Air Force for the rest of the war. Since most of it was made of wood or plywood, this meant that the production could be outsourced to workshops that could not otherwise contribute to the war effort in a decisive way.

A Mosquito of 456 Squadron RAAF (Royal Australian Air Force): Photo Royal Air Force

Did Bo Lundberg know about the DH 98 project? He should have been aware of the de Havilland DH 91 Albatross passenger aircraft, at least. This was off composite construction using a lot of wood, which was the starting point for the de Havilland company when it started to design what would become the Mosquito.

Swedish aircraft in China and the Philippines

While the J9 aircraft intended for Sweden ended up flying for the USA in the Philippines, there was not much US interest in the J10, the Vultee P-66 Vanguard. All but two of the aircraft that had been produced had been ordered by Sweden, and neither the US Army nor Navy (there was no independent US Air Force yet) were interested in increasing their logistical problems by yet another type of aircraft. To start with, Great Britain had initially agreed to take 100 aircraft, which would be used as advanced trainers, but backed out before a deal was struck.

About 50 P-66 aircraft were in the end sent to a US Army Air Corps fighter squadron outside Oakland, California, and never saw action. The remaining aircraft were finally sent to China, which had since 1937 been engaged in a bitter war with Japan and was in desperate need of war material, not least aircraft. Unlike Japan, Chinas had not succeeded in setting up domestic manufacture of modern war material and was also split into several factions which even fought against each other. The two largest, the Communists under Mao Tse Tung and the Nationalists under Chiang kai-shek, called for a ceasefire in order to be able to fight more effectively against the Japanese, but both groups had problems with acquiring weapons, even though both the Soviet Union and the USA sent war material as aid to China.

A Vultee P-66 of the Nationalist Chinese Air Force being serviced by ground personnel

In the meantime, the USA, before being pulled into the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7th, contributed with a large voluntary group of pilots, the AVG or American Volunteer Group, which received the nickname “The Flying Tigers” after the shark mouth emblem they painted on their Curtiss P-40 Warhawks. This group was established under the auspices of the USA and included American military pilots from the US Army. Navy and Marine Corps with the blessing of their military branches, similarly to the Swedish No. 19 Wing that took part in the Finnish Winter War 1939-1940.

A P-40 belonging to AVG ”The Flying Tigers” displaying the sharks mouth emblem. Photo: San Diego Air and Space Museum.

Out of 128 P-66 aircraft built, 104 arrived in Karachi in Pakistan at the end of May 1942, where they were received by Chinese pilots. As the American flying instructors were fully occupied in teaching other Chinese pilots to fly the Curtiss P40, the P-66 pilots were obliged to self-teach, with several accidents as a result. 79 P-66s eventually made their way to Chengdu in China. They began to be placed in combat in October 1942, but many remained on the ground with tools and spare parts lying unused in storage. During 1943 these aircraft were engaged more often, not least fighting Japanese bombers, and unfortunately a number of P-66 aircraft were shot down due to being mistaken for Japanese Nakajima Ki-43 Hayabusa fighters. They also had difficulty in intercepting the Japanese fighters. The P-66 gradually became replaced by the Curtiss P40, an aircraft that became an icon, particularly because of the shark mouth emblem that was made popular by the “Flying Tigers” of the AVG. On the whole the P-66 revealed its deficiencies, and it was perhaps just as well that it never flew in Sweden.

The J9s and the terrible fate of the 34th Pursuit Squadron

The J9s that should have equipped No. 9 Wing in Gothenburg also became victims of the USA’s weapons embargo. The Republic company hoped all along that the embargo would be cancelled, and completed 60 Republic Seversky P-35s to the Swedish specifications. But in October 1940 these aircraft were simply impressed into the US Army Air Corps and designated P-35A. Most of them were then sent to the Philippines after slight modification. This meant that most of them had Swedish flight instruments, and in some cases still wore the Swedish national insignia!

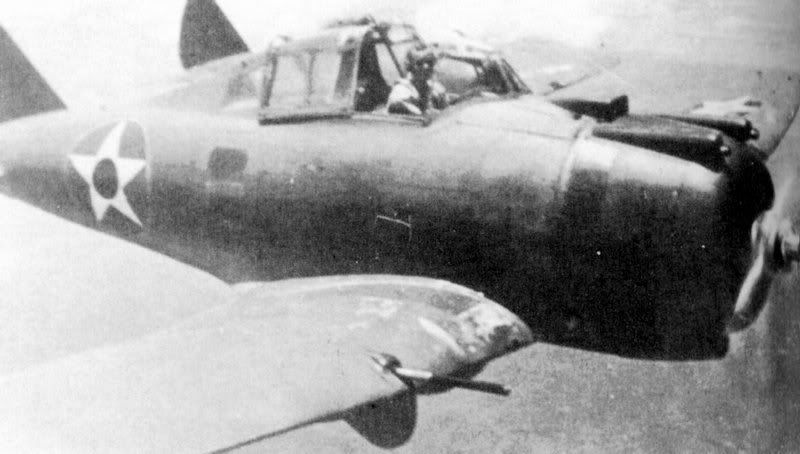

The plan was to transfer these aircraft from the USAAC to the Philippine Air Force after more Curtiss P-40s had been delivered, but in November 1941 a further two Squadrons were sent from the USAAC to the Philippines, the 21st and the 34th Pursuit Squadrons. These temporarily took over the “Swedish” aircraft while waiting for more P-40s. In December 1941, just as war broke out in the Pacific, the 21st Squadron received its P-40s and their remaining P-35s went to the 34th Squadron. This is how the aircraft originally destined for Sweden became involved in the desperate battles resulting from the Japanese invasion of the Philippines.

A P-35 of the 34th Pursuit Squadron over the Philippines. Photo US Air Force

34th Pursuit Squadron joined the battle and it became apparent that the P-35 was outclassed by the Japanese Navy’s Mitsubishi AM6 “Zero”. The P-35s had no armour protection for the pilot nor self-sealing fuel tanks, which made them particularly vulnerable. On December 10th 1941 the Japanese aircraft mounted a large surprise attack against the Del Carmen air base, where the 34th Squadron was based. 12 P-35s were destroyed and 6 damaged in just that one attack. Two days later only 8 P-36s were airworthy.

The P35s fought back as well as they could, and on December 10th Lieutenant Samuel H. Marrett sank the Japanese minesweeper W-10. Marrett, who was the 34ths commanding officer, led the remaining P-35s in an attack against landing Japanese forces. Two transport ships caught fire during the repeated attacks and W-10 exploded when Marrett made yet another attack. The explosion even damaged his aircraft and Marrett was killed when it crashed. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy in the Philippines.

The remaining pilots continued to fight with what aircraft were left. One by one the aircraft were destroyed and their pilots were killed or injured. On January 11th 1942 the last two flew to Mindanao, with passengers crammed into the baggage compartments. The ground crews then fought as infantry in the defence of the Bataan peninsula.

On April 4th the two P-35s returned to evacuate more personnel from Bataan, but one crashed on the way back. Now there were no volunteers left who could fly the last aircraft, with the designation Nr 23, so it was handed over to Captain Ramon Zosa of the Philippine Air Force. On May 3rd he set off in P-35 Nr23 together with a single P-40 to attack Japanese landing forces. Zosa and his P-35 were shot down during the attack.

Airplane nr 23, the last of the P-35:s in the air. The wear and tear of combat is clearly visible. It is unclear wether the pilot is Captain Ramon Soza or an american pilot.